the Silhouette

the Silhouette

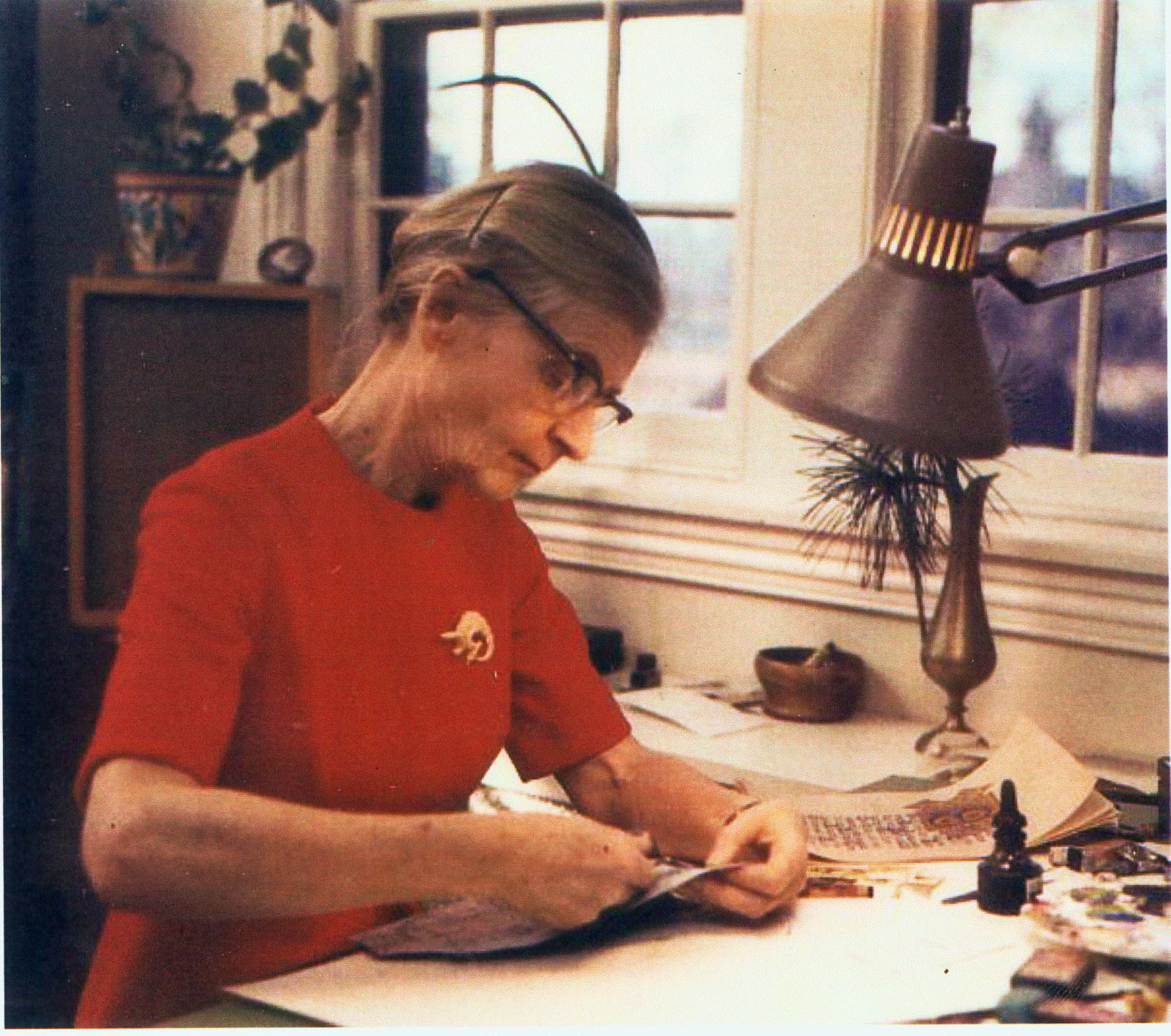

utting holes into a piece of paper may be fun for half an hour to your average citizen but making a life’s work of it is not for everyone. The way I remember my mother, she is sitting on a chair just like in the photo and looking intently at the work in her hands, concentrating and constantly rotating the paper around her tiny scissors, as she cuts away everything that isn’t the flower or the insect or the likeness of a person. Gradually, over a period of hours or days, that paper turns into a spidery ball, which only she will be able to disentangle at the end. Paper, when cut as finely as she was able to, will deform; it will stretch along the line of cutting. That’s why it balls up and that’s why she will have to push it gently back into its original plane, when all the cutting is done and she glues it onto a background. As she sat there and worked, she hated to be interrupted and did occasionally ask me to tell a would-be gossipy visitor that she wasn’t in. But she liked to smoke cigarette after cigarette and listen to classical music being broadcast by one of the many European stations within reception range of our small black plastic radio. On Thursday evenings the local librarian, Miss Erdmann, came to visit and read Dostoevski’s novels to her until late into the night. My father, accepting her as the primary breadwinner during long periods of their marriage, did all the housework of shopping and cooking and laundry. Both my father and she were enthusiastic nature lovers. Often he would find a wild flower or an insect on his walk to the grocery store or other errand and hand it to her with all the air of offering her a Tiffany jewel. She would grow ecstatic about the gift, admire its color or its fantastic shape and declare right there, that she must draw it immediately. If it was a bug or a butterfly, he would now have to sit under a glass for maybe half an hour before regaining his freedom. If it was a flower, it would be put in a vase on her drawing table. As she drew, she might pencil shade an area on her very detailed drawing to help her remember that this was a dark place or she might even make small notes about light or dark areas. She was lucky that my father was a craftsman who knew how to hand sharpen her many small scissors. Their points could not stay sharp for long with all her intensive stabbing and cutting. The kind of paper, that she had to use because it could stand up to such abuse, would be heavily filled and abrasive to tools. After the war, when there were no artist supplies available, she found that blue print paper, such as architects employ, was the strongest; it didn’t matter if had been exposed. She would make her drawing on one side and brush India ink on the other side. Occasionally she might add little cutouts of silver or gold paper (aluminum foil from her cigarette packs) for accents. by Lars Christian Luther, son of Margarethe |